Revolutionaries are sometimes forgotten, despite their mission having been successful.

Their struggle over, it’s often condensed to a single heroic figure, recast by history into a

pacifist and a statesman. Nelson Mandela, for example.

Revolutionaries unable to overthrow their oppressor or if they build a state that doesn’t

comply with western interests, are dismissed as radicals, even terrorists. Shoved to the

backside of history.

Mandela is rightly celebrated as a remarkable individual at multiple levels. None

question his crowning. Yet, among forgotten revolutionaries are his fellow militants, members

of MK –uMkhonto weSizwe, People of the Spear. This was the militant wing of the African

National Congress founded by Mandela himself. (A fact often overlooked.) MK continued the

costly yet essential armed struggle moving through stages of successful sabotage actions, then

decline, exile, followed by revival and importance. It continued while Mandela was in prison.

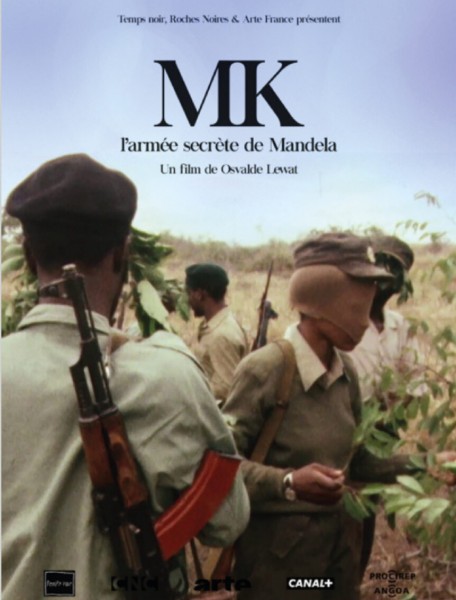

Ms. Osvalde Lewat, the Franco-Cameroonian director of the 2022 film MK-Mandela’s

Secret Army, opening in New York, taps the memories and sentiments of veteran MK fighters.

She weaves their gently-proud testimonies with (almost lost) footage of MK’s secret military

training camps outside South Africa. The women and men interviewed here joined MK during

the critical years after 1961. The Sharpeville Massacre that year marked a turning point when

ANC leaders Mandela and Oliver Tambo decided “the time has come that the black masses, all

25 million, should join in one determined offensive…”.

“…We tried to solve problems with other methods”, Tambo continues (in a archived clip

in the film); “Since these were not forthcoming, we must solve problems with what is available

to us; and the stage that’s been reached (that’s) … available to us now, are those methods of

violence…used against us, because the worst of all horrors in the world is to live forever as a

slave, as hated, despised, subhuman; and this we reject”. Words reinforced by Mandela’s

assertion (also documented here) – “…Armed struggle for the freedom of Black South Africans

rose after years of unsuccessful mass demonstrations and after the white apartheid regime

responded to (our) non-violent actions with increased violence.”

This film’s history of MK opens with rousing yet calm declarations sung by MK fighters,

some no longer living, affirming: “We are more powerful than apartheid”; “We come from the

bush”; “We will defeat you”. Ex-fighter Dudu Msomi recalls her mother’s response to her

decision, when barely out of her teens, to join in armed resistance: “Because anyway you living

in this country, you are going to die”: “We have two choices: submit or fight… Submit or die”,

asserts Zola Maseko, another veteran.

These statements cannot be heard without realizing the background, motive and logic

of Palestinian resistance that is hardly uttered behind the flood of current news stories of the

war presently underway in occupied Palestinian fields, homes and schools. Like the ineffective

Black civil mass resistance that forced the shift to armed resistance led by MK’s militant cadres

half a century ago, Palestinian resistance arose after Israel’s decades-long apartheid rule. This

film’s images of beatings, jailings and shootings of Black protesters by South Africa’s apartheid

troops, shocking to view, are surpassed by the genocide underway in Gaza today. Accounts of

terror imposed by South Africa’s apartheid forces parallel Israel’s oppressive measures (noted

by Mandela’s grandson in 2019) that confine the population into ghettos, imprison and kill with

impunity, humiliate, usurp land, and thwart economic independence – all carried out year-

after-year without hope of relief or even a modicum of self-rule. In both places, resistance was

labeled terrorist, its leaders denied a voice in international forums.

The decline and downfall of South Africa’s apartheid regime entered western

consciousness after years of armed struggle, and then only within the boycott movement.

(Palestinian’s BDS drive has limited parallels.) When the boycott of South Africa gained

momentum, those joining as late as 1985 credited Pretoria’s policy change to their efforts.

Meanwhile MK, Mandela’s Secret army’s ongoing role was subsumed. Veteran MK fighter Mac

Maharaj explains that co-opting: “The idea that Mandela should be portrayed as a pacifist is

again to appropriate our history and place it in the model of a colonial mentality.” He continues

to insist, “The foremost truth about Mandela was that he was a freedom fighter”

In a recent interview in Africultures, the filmmaker herself asserts “It’s hard to

remember that this (victory) was achieved at the cost of thousands of lives sacrificed; but it is

essential to remember that it was not just the good conscience of the West (through embargo

action) that suddenly woke up”.

Ms. Lewat explicit goal is to amplify and uphold uMkhonto weSizwe’s essential role in

overturning the hated South African policy. “In South Africa as elsewhere, their importance in

the anti-apartheid struggle is little understood. This film is to fill this recognition gap” and

“move away for the polite image of Nelson Mandela”.

It’s surprising to learn from Lewat of her difficulties in locating MK’s archives. “… Lack of

images reveals the lack of communication about the MK”. Footage shot in MK’s foreign-based

training camps have recruits learning guerrilla tactics, topography, explosives, tank and gun

operation, their rigorous training reinforced by dances and rallying calls, shouts and praises that

sustained soldiers. (Their poetic compositions somehow relayed to Blacks at home helped

inspire new recruits.) Gathering personal testimonies from veterans was more difficult than

might be imagined. Lewat notes in her 2023 Africulture interview that many veterans were

unwilling to discuss the disappointing aftermath of their struggle. After the peace agreement,

they were marginalized and psychologically damaged. They found themselves economically

destitute, especially when they refused to participate in the much-celebrated Truth and

Reconciliation Commission.

Nevertheless Lewat found seven men and women, all MK veterans, to join this film

history. Moving, proud testimonies, even their delight in their earlies sabotage efforts that

targeted electrical transmission towers and military bases, give an overarching reality to the

struggle. Their quiet, reflective comments form the film’s backbone. With subdued bitterness

they recall sustained torture and imprisonment, the lost comrades, the sacrifice of families, and

their own dismay over fellow cadres having been cast aside. The pride and candor of their

testimonies is surely their final effort to validate the role of armed struggle. And where is

Mandela himself? Lewat makes clear that her motive was to reject MK-founder’s sanitized

image, but to recognize “Nelson Mandela had been at the origin of the creation of an armed

wing, that it was he who had pushed the ANC, which was a peaceful party, to violence.” This

discovery was her motive for this new contribution to African history and resistance

movements.

MK-Mandela’s Secret Army, premiers Nov. 26 at the African Diaspora International Film Festival

in NYC is distributed by https://ArtMattanFilms.com