Local law enforcement agreements with ICE not yet impacting operations in Michigan

By Douglas P. Marsh

Originally published at MichiganAdvance.com /2026/01/08/federal-incentives-fuel-closer-ice-partnerships-with-michigan-police-agencies/

The fatal shooting of a Minneapolis woman by an Immigration and Customs Enforcement officer on Wednesday—after the agent fired through the window of her car—has renewed national scrutiny of ICE’s expanding role and the growing involvement of local law enforcement in federal immigration operations.

As federal immigration enforcement expands nationwide, a growing number of local law enforcement agencies, including in Michigan, are entering formal agreements with ICE, potentially reshaping the relationship between federal and local policing. The Minneapolis shooting, reported as ICE officers were attempting to stop a vehicle, has intensified concerns among civil rights advocates about accountability, use of force, and the spillover effects of immigration enforcement into routine policing.

Since October 2025, when the Department of Homeland Security began offering financial incentives such as salary reimbursements and performance-based awards, participation in ICE’s 287(g) program has accelerated.

In Michigan, where seven agencies have signed agreements under different enforcement models, police chiefs and sheriffs say the partnerships largely formalize long-standing cooperation with federal authorities—setting the stage for renewed scrutiny of a program with a long and contested history.

Separate federal offices used to administer immigration and naturalization in the United States. They were consolidated into the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, or INS, in 1933, initially under the Department of Labor, later transferred under the Department of Justice in 1940.

The INS rebranded as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and moved under the auspices of the newly established Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in 2003.

Section 287(g) was added to the United States Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1996, and outlined how state and local law enforcement agencies could establish agreements with INS/ICE. These agreements allow local law enforcement officers to “perform a function of an immigration officer in relation to the investigation, apprehension, or detention of aliens in the United States (including the transportation of such aliens across State lines to detention centers).”

Recent data released by ICE shows active agreements dating back to 2019, when law enforcement agencies in Florida began signing up, followed by Texas and other states later that year. To date, Florida and Texas law enforcement agencies comprise more than 60% of those with agreements in place.

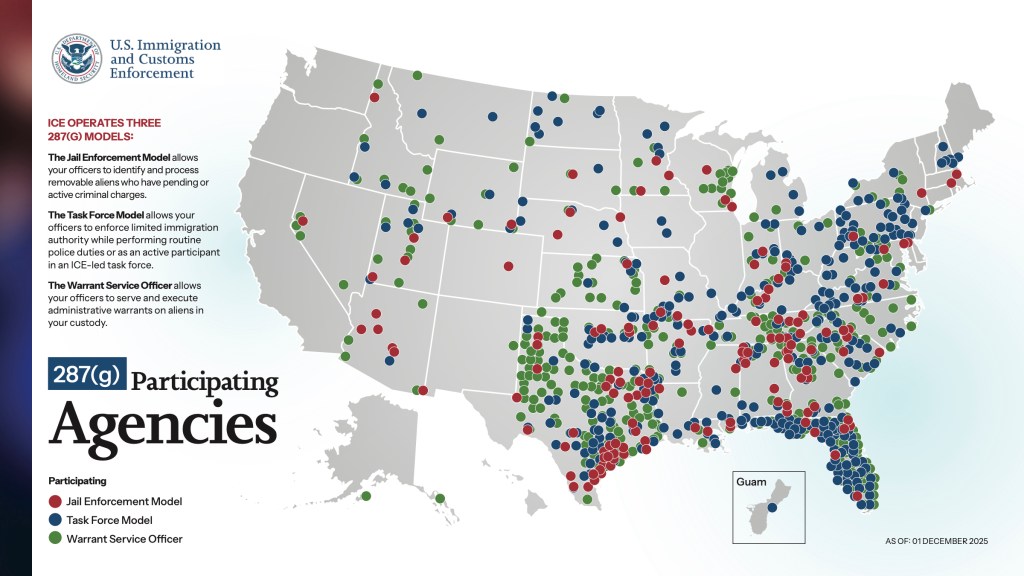

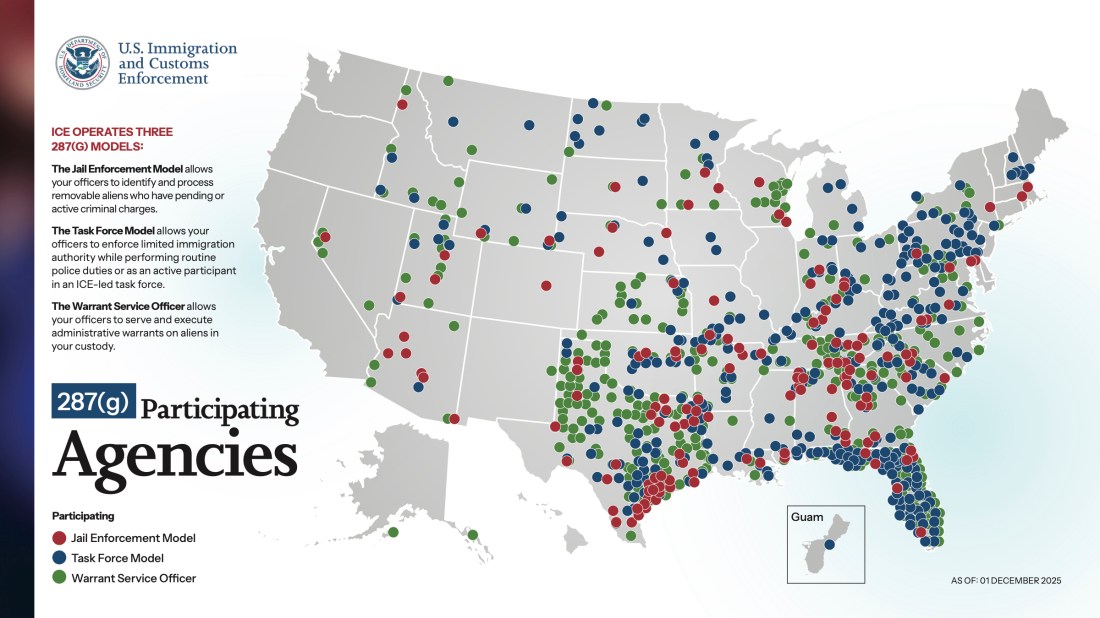

As of December 30, 2025, ICE reported maintaining 1,274 agreements with 975 agencies in 46 states—some agencies maintain several agreements, as they take several forms, or models.

Models, training and certification

Existing agreements fall under three models: jail enforcement, warrant service officer and task force. A fourth model, tribal task force, was added in December 2025. All but 134 of the active agreements were signed after the Trump administration brought back the task force model, which had been discontinued in 2012 after the Department of Justice (in North Carolina and Arizona) and independent researchers found cases of racial profiling and patterns of constitutional violations.

More than half of agreements in place today are under the task force model.

The Jackson County Sheriff’s Office has the oldest active 287(g) agreement in Michigan, having signed in March 2025 under the warrant service officer model. The sheriff’s offices in Berrien and Calhoun counties later joined under the same model.

“The jail enforcement model requires deputies to attend training out of state and with current staffing levels we did not see this as a good option for us at this time,” said Berrien County Sheriff Chuck Heit. “The task force model also requires extensive training out of state and would then give us the authority to enforce immigration law ourselves, which is not an option I am interested in at this time.”

The warrant service model requires the least training.

“This program only pertains to individuals who are in our custody at the Berrien County Jail,” said Heit.

He said the program would streamline processes already in place to execute ICE administrative warrants.

“We have cooperated with ICE for over 20 years in holding inmates for up to 48 hours,” he said. “The safest way to deal with an immigration warrant is when the individual is already in custody.”

In late December, both Heit and Jackson County Sheriff Gary R. Schuette said they were still waiting for ICE to complete training for jail staff.

“It’s kind of on them,” said Schuette. “Ball’s in their court.”

“We are looking at getting six of our staff trained in the warrant service officer program,” said Heit. “We are looking for this training to occur in early 2026.”

Local immigration enforcement in theory and practice

Located south of Detroit, the City of Taylor Police Department signed the oldest active 287(g) memorandum of agreement in Michigan under the task force model, entering the MOA in late April 2025. Sheriffs in Roscommon and Crawford counties followed, while in nearby Ogemaw County, in November 2025, the City of West Branch became the most recent agency in Michigan to sign a 287(g) task force MOA.

The task force model requires the most training and the agreement language authorizes a number of immigration enforcement actions for a certified local law enforcement officer. These include arresting and interrogating suspected aliens without a warrant, serving and executing warrants of arrest for immigration violations, taking and maintaining custody of and transporting aliens arrested by ICE.

Police chiefs in West Branch and Taylor said the program has not impacted their operations.

“287(g) doesn’t change a thing,” said Taylor Police Chief John Blair. “If we come into contact with someone who’s in the country illegally, we’ll contact ICE.”

Blair’s career in law enforcement involved coordinating with Customs and Border Patrol before ICE was established. He said cooperation with federal agencies, which themselves support local law enforcement, is natural.

He also acknowledged that training and certification present a challenge.

“The training is free but they’re not paying your guys to go to the training,” he said. “Time away from the responsibilities was a problem.”

“It doesn’t change anything that we do now,” said West Branch Police Chief Ken Walters, responding to a local resident at a city council meeting. “If we come into contact with an illegal alien right now on a criminal complaint—traffic crimes, any of that—that individual has always been taken into custody. Then they’re lodged in the county jail and then border patrol or DHS [ICE] would come and get them from the jail. The only difference is in the cooperative agreement, we’d do the transport to their facility.”

Perspectives on the 287(g) program

The Genesee County Sheriff’s Office and City of Center Line Police Department had signed MOAs earlier in fall 2025 but quickly rescinded them, the former citing changes in staffing duties. In Center Line, the mayor and city council withdrew from the agreement after public pressure.

“After listening to the public comments and discussing the 287(g) MOU with City Council members and the Mayor of Center Line, the City Manager has determined that it is in the City’s best interest to withdraw its MOA with ICE,” said the city in a public statement.

Berrien County Sheriff Chuck Heit, like Taylor Police Chief John Blair, reported a healthy working relationship with federal agencies.

“We have cooperated with ICE for over 20 years in holding inmates for them who have a valid hold just like we do for other agencies and jurisdictions,” he said. “We have a great working relationship with our federal law enforcement partners and will continue to assist each of them.”

Berrien County Undersheriff Greg Sanders suggested local immigration enforcement within the confines of the jail is preferable, “as opposed to having agents come to town and try to locate individuals out in the community.”

But in Texas, where state legislators mandated that all sheriffs participate in the 287(g) program, federal agent presence has not decreased.

“We’ve seen the contrary,” said Osvaldo Grimaldo, a policy and advocacy strategist with the ACLU of Texas. “As we’ve seen an increase in 287(g) agreements with our county sheriffs, we’ve also seen an increase in federal immigration agents in areas where 287(g) agreements have been signed or are going to be signed.”

Grimaldo said many agencies are compelled to join under the task force model.

“When it comes to police departments and other agencies that don’t run their own jail, that’s the only model that’s available to them,” he said.

Guidance to law enforcement agencies from the Michigan ACLU, updated in September 2025, observes that “[w]hen noncitizens perceive that local law enforcement agencies are helping to enforce federal immigration law, rather than prioritizing public safety in their communities, they may be less likely to reach out to police or sheriff’s departments when they are witnesses to or victims of a crime, because they fear that they or their loved ones might end up detained and deported.”

The guidance document notes that the term noncitizen “includes individuals who are not (yet) U.S. citizens—such as those with temporary status, legal presence, or permanent residency.”

The latest information on the 287(g) program is available at www.ice.gov/identify-and-arrest/287g.

I Think Nancy & Stephanie Sidley are an apologist for United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement

LikeLike

I Think United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement Is on the same level as the Proud Boys, Ku Klux Klan, Jewish Defense League, Jewish Defense League, Earth Liberation Front, The Covenant, The Sword, and the Arm of the Lord, Atomwaffen Division, Aryan Nations, Army of God, Animal Liberation Front, Alpha 66 and Omega 7, 764 and No Lives Matter, May 19 Communist Organization, The Order, Phineas Priesthood, Symbionese Liberation Army, United Freedom Front, Weather Underground,

LikeLike

nice work. Dangerous times.

LikeLike